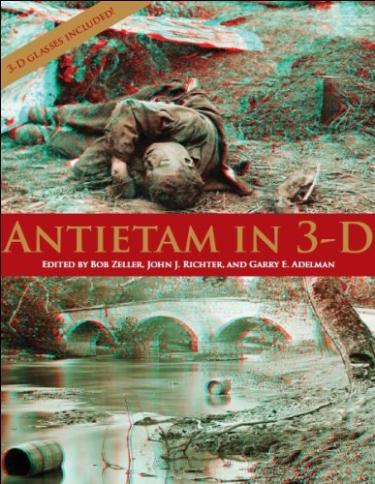

Book: Antietam in 3-D

The Civil War Trust recently had the opportunity to talk with Civil War photography experts Bob Zeller and John Richter, two of the editors of the new book Antietam in 3-D. The pair also collaborated on their 2010 book, Lincoln in 3-D.

Civil War Trust: Antietam in 3-D? Has this been done before?

Bob Zeller: No one until now has ever published a book exclusively devoted to the stereoscopic photography at Antietam. Forty of the 44 pages in the book are devoted to Alexander Gardner’s 3-D photos of Antietam, including his history-making first images of American dead on a field of war. We feature 50 Gardner photos, including 15 of the dead. Three of my previous 3-D books have featured Antietam photographs in 3-D, but only a small selection.

John Richter: A couple of other unique features from the book: we have a 3-D map showing all the known camera locations for the images in the book. We also paired two woodcuts, which appeared in the newspapers at the time, with the stereo views that they were made from. One of the views shows a Union grave alongside the body of a Rebel soldier. Gardner’s original caption was “A Contrast”. That caption could be used today for our pairing of the flat woodcut and the very realistic 3-D photo it was made from.

What’s the gimmick here? How did you turn 150 year-old photos into 3-D pictures?

BZ: These 3-D photos are as authentic to the Civil War as the strictest reenactor’s uniform. Most of Alexander Gardner's photographs at Antietam, including all 20 images he took of the dead, were taken in 3-D, published in 3-D and meant to be seen in 3-D. And many Americans saw them that way during the war. Of the 120 documented photographs Gardner and his assistants took in and around Antietam during the Maryland campaign in the fall of 1862, 85 were shot in 3-D. Unfortunately, the fact that most Civil War documentary photographs were shot in 3-D was all but lost during the 20th century. None of the books I grew up with gave any indication that the dramatic photos they contained are mostly 3-D photos. This was the secret about Civil War photography that Ken Burns didn’t tell you about in his landmark documentary The Civil War.

Why were Civil War Photographers taking pictures in 3-D?

JR: Civil War photographers in the field were business men and stereo views were a big part of that business. During that time newspapers were unable to reproduce photographs so the only way a person could really see faraway lands or important events was through stereo views.

BZ: The stereoscopic image was the video of Civil War America. It was one of the first forms of mass-marketed home entertainment for the American parlor. On the eve of the Civil War, around 1859, stereo-mania was sweeping the country. The advent of the collodion glass plate photographic negative allowed, for the first time, the creation of limitless prints from a single negative. Mass marketing of photographic images became possible, and exploded in popularity in both the North and the South even as the tensions grew to a fever pitch. Gardner sold them as stereo view cards. The Antietam series was numbered, and one could collect them like people collect sports cards today.

The 3D glasses in the book are of the red/cyan variety. Is that the only way to see these images in 3-D?

BZ: No, there are a number of methods. Civil War Americans saw their 3-D views through the convergent lenses of a stereo viewer, peering at a card that contained two side-by-side photographs that, when combined in the viewer’s brain, gave the optical illusion of depth. You see in 3-D because each eye sees a slightly different view. If you have a camera with two lenses an eye-width apart, the two images produced by those lenses will work together in 3-D. Today, there are a number of different methods to project and view 3-D images, including the red-cyan anaglyph method we use in the Antietam book. That’s the most common way. Other methods include the use of polarizing lenses and the use of high-speed shutters.

Many of the photographs focus on scenery or on soldiers doing things that seem very routine (resting, talking with friends, etc.). Can you explain how Civil War photographers determined their subject-matter? Were these pictures posed?

JR: Since every photo was taken as a time exposure, with the camera on a tripod, it limited what you could record. In that sense they were posed, as anyone in the photo had to hold still. But they were very clever in overcoming that handicap by the wide variety of scenes that they recorded. The closer you look at the photographs the more little details you see, in the backgrounds, etc. There’s a lot more going on in the views than what you would expect from the cumbersome equipment they had to use.

How did these early photographers differ from modern-day war correspondents?

BZ: Alexander Gardner was an honorary captain on Gen. George McClellan’s staff. Civil War photographers were more apt to do work for the armies, particularly photographic map copying. They generally avoided going into harm’s way (or perhaps were not allowed to) because the photographic technology they had in the field limited mobility and required exposures of several seconds or more. Although the first action photographs were taken during the war, they were taken at a distance.

JR: Working with a digital camera, modern correspondents can take a thousand pictures and then pick their best ones. A Civil War photographer wasn’t trying to convey a message, but just set up and get a good photo that they could sell. Travelling by wagon and hauling all your equipment along, setting up the camera, coating the plate, etc. all took time. You had to make each shot count, you thought about where you would set up the camera, figure the exposure, etc. I think it was a purer form of photography.

Did the images captured by Civil War photographers have any significant influence on the home front or on the way Americans thought about war?

BZ: They gave the first glimpse to the homefront of what the war was really all about, particularly Gardner’s Antietam photos. “If Brady has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it,” wrote a New York Times reporter who visited Brady’s gallery about a month after the battle of Antietam, where people were lining up to see the sensational photographic exhibition, “The Dead of Antietam.” Civil War Americans were used to photos of the dead because it was a fairly common practice to take a final photograph of a deceased loved one before they were interred. But these images of bloated, torn, misshapen corpses scattered on a battlefield as they fell were unlike anything anybody in America had seen, and they caused a sensation. There is no evidence, however, that they caused any sort of outcry against the war, as did the television newscasts that brought the Vietnam War into American living rooms on a nightly basis.

Many of the pictures focus on of graves, grave-diggers, and casualties. Why is it important for people today to see these somber images?

BZ: To see the true cost of war, for one thing. And to be able to understand history by actually seeing it. The photographs of the American Civil War allow us to bond to that conflict and visualized it so much more vividly than the Revolution. Photography and preservation go hand-in-hand in allowing us to conjure up what it really must have been like. You not only have a place called Bloody Lane at Antietam, you have photographs of it that vividly show why it got its gruesome name. And because Antietam is largely preserved, you can go to that exact spot where those bodies lay, and where Gardner set up his camera. It’s a visceral, palpable connection.

Is there anything else that looking at photographs in 3-D teaches us about the Civil War? What did this book project teach you?

JR: For me it makes it more real. Looking at a 3-D Civil War photo is as close as you’re going to get to being there. I think you make the connection, a drawing or painting just doesn’t have the impact that a 3-D photo has.

BZ: It lets you see the war’s imagery in a whole new way – a more sophisticated and detailed way. You don’t just glance at a stereo view; you let yourself experience it. “The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture,” wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes, who co-invented the inexpensive hand-held stereo viewer. The book project taught us that you can, indeed, really adapt the vintage 3-D to modern technologies for an even more spectacular viewing experience than seeing original stereo views.

How did you first get interested in Civil War photography? Why 3D?

JR: As a kid I had a View-Master 3 reel set of Civil War scenes made from the Library of Congress negatives. It was a revelation to see those familiar scenes in 3-D. As time went on I discovered they were originally issued as stereo views, so I started to collect those. 3-D has always been my time machine, you can be transported back through so much history and it’s like you’re standing right there alongside the photographer.

BZ: The first antique I ever owned was a hand-held stereo viewer that I bought for about $4.50 at age 13 at a local antique show my mother took me to. After that, I would always look for stereo views at antique stores. And I was quite fond of my stack of stereo views of the old West and other scenes. But I did not know of the existence of Civil War stereo views until I was 28 years old. Somehow, that knowledge had eluded me. In 1980, when the late D. Mark Katz, a Civil War photo dealer and author, showed me my first Civil War stereo view – a vintage original Gardner view of Sunken Road at Antietam – my jaw hit the floor. I could not believe such a thing existed. I bought that view on the spot and began collecting Gardner’s Antietam photos. And after more than 30 years of collecting, I have more than 50 vintage original Gardner stereo views of Antietam. Almost a third of the stereographs in the book come from original prints in my collection.

Do you have a favorite 3-D image in this book?

JR: Lincoln and McClellan in the tent at Antietam. Any 3-D photos of Lincoln are magic.

BZ: In terms of this book, I think that no Antietam image shines with greater clarity and brilliance – in all of its 3-D glory – than the image of Gen. John Caldwell and his staff in camp in the East Woods on page 35. That is such a magnificent image and it’s never been better than in this book.

This isn’t the first book of Civil War Era 3-D photography for either of you. Do you have plans for any more?

JR: We’re just getting started! We’ve barely scratched the surface of available Civil War 3-D photography. Bob and I both know of scores of original 3-D photos that haven’t been seen since their original publication.

BZ: We are so thrilled at The Center for Civil War Photography about how this book has come out, we are tentatively planning to publish Gettysburg in 3-D in time for the 150th anniversary in 2013.

Buy the Book: Antietam in 3-D is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Writer and historian Bob Zeller is one of the country's leading authorities on Civil War photography. He is the author of The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography (Praeger, 2005), the first narrative history about the war's photographers, what they did and why they did it. Zeller pioneered the modern presentation of 3-D Civil War photography with The Civil War in Depth (Chronicle Books, 1997), the first 3-D photo history of the war. His latest book, in collaboration with John J. Richter, is Lincoln in 3-D (Chronicle Books, 2010). Bob spent 25 years in newspaper journalism, specializing in investigative reporting and later working as a motorsports beat writer covering NASCAR. Bob, 60, a native of Washington, D.C., has published 10 books and has been presenting lectures with 3-D slide shows of original Civil War photographs since 1997. He lives in North Carolina with his wife, Ann, who is the city manager of Troutman.

As a child, John Richter became aware of the use of stereo photography during the Civil War from his first View-Master set of views taken from Library of Congress negatives. This first exposure to 3-D photography fed his already fervent interest in the Civil War because those views were of familiar Civil War scenes - but with depth! Hooked on the 3-D experience and growing up 15 miles from Gettysburg, it wasn't long until John focused on Gettysburg and began building his world-class collection of period stereo views. Views from his collection have appeared in Tim Smith's John Burns: The Hero of Gettysburg, Garry Adelman's The Myth of Little Round Top, both volumes of Bob Zeller's The Civil War In Depth, and The Blue and Gray in Black and White among others. John has written for "Stereo World" and co-edited the "CCWP's 99 Historic Images of..." series of booklets. John is a long time stereo photographer and member of the National Stereoscopic Association, the International Stereoscopic Union, and Director of Imaging for The Center For Civil War Photography. Much of John’s work includes digital restoration of original images. He has produced 3-D displays for the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, Gettysburg Visitor Center, Pamplin Historical Park, Maryland Historical Society, Atlanta History Center, Canton Museum of Art, Pry House Museum, and the Smithsonian. He has co-produced, along with CCWP President Bob Zeller, a fully digital 3-D projection show "Lincoln In 3-D." The show, comprised of 180 historic images, is a 40-minute program that provides a comprehensive stereo photographic history of Lincoln's presidency. John has also coauthored the companion book, Lincoln In 3-D, published by Chronicle Books.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316